The Bower & Collier Family History

Research by Colin Bower

Bower Family Tree

THE STRUCTURE AND DEVELOPMENT OF COMMERCIAL GARDENING BUSINESSES IN FULHAM AND HAMMERSMITH, MIDDLESEX, C. 1680-1861.

BARBARA ANNE ROUGH, WOLFSON COLLEGE, UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE SEPTEMBER 2017

Extract frrom Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of History for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy

THE BOWER FAMILY AT ROWBERRY MEAD

"A longitudinal view of one small plot on the bishop’s estate over a 100 years illustrates the advantages of being a head lessee.

Rowberry Mead was 5 acres of garden land on the bank of the Thames It had been converted from meadow to garden sometime before 1761,but the annual reserved rent of £8 had not been adjusted to reflect the higher earning potential of garden land and remained at the level in the 1647 parliamentary survey.

The Bower family had a long connection with land around Rowberry Mead. A Mr Bower was in the 1757 highway rate book for the cherry orchard late Thompson’ on adjacent land.

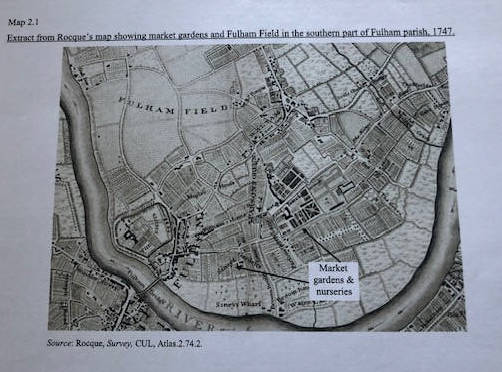

1747 Map Of Fulham

A map from the Dissertation shows Fulham Field, top left the area known as Crab Tree and further south the cherry orchard can be seen:

The Bowers then disappear from the records for a few years. From 1761 Mr Cobb, a draper in Drury Lane, Westminster, held a life tenure on the Mead. This lapsed with his death in 1796 and ‘the Bishop thought proper to grant it upon 21 years’ as a new lease to William Bower.

Bower had sub-let from Cobb since at least 1782 as that year he paid the land tax as Cobb’s tenant.

Table 4.2 shows Bower paid £170 based on a standard entry fine of 14 years purchase and an economic value of £20.3s.0d plus £13.10s.0d in fees. This must have been an acceptable arrangement as he renewed the lease after 7 years had elapsed, and paid a fine of £18.15s.0d based on 1.25 years net annual value.

Table 4.2

Rowberry Mead was surveyed in 1809 and the report gives a picture of the garden. There was ‘a small timber board and tiled dwelling house; a timbers, board and tiled Ware Room, with a Stable, under one roof, and a cart shed’.

The new valuation of £26 per annum was made up of £5 for the house and outbuildings; £2 for 1 acre of ‘banks and boggy land’; 3 acres of ‘occasionally wet land’ at £4 per acre; and 1 acre of ‘the driest part of the land’ at £7 per acre, with a third of an acre of ditches and the site of the buildings ‘gratis’. The variation in rent, dependent upon the quality of the garden land, highlights one of the difficulties in evaluating and comparing rents for a parcel of land.

The surveyor was not very impressed with the suitability of the land for a garden business:

"This may be considered a Casualty piece of land for garden ground: In dry years it may be very productive but can never have an early produce from it’s low situation and being subject to floods I think it would be worth as much in Grass as it is in it’s present mode of cultivation."

William’s wife inherited the lease in 1816 and in her will in 1820 she mentioned her ‘eldest son George Bower having been provided for’. At the next renewal in 1823 George was granted a 21 year lease.

Another survey in 1837 valued the property at £40.673 Despite the earlier disparaging remarks the garden had continued for a further 28 years and the new surveyor was slightly more optimistic:

"The land before alluded to although it is embanked against the River is subject to the inundation of the high Tides as well as of the water forcing its way through and injuring the banks which occasions an expense to the tenant in making good the same; also damage to the crops on the ground in Winter, by rendering the earth wet and cold. Nevertheless, the soil is fertile and produces good crops in the summer season."

As a result the surveyor made an allowance for the £2 Bower had paid to repair the embankment when assessing the net economic rent for the next renewal fine. George died in 1845 and his son, also George, took over. In 1851 he was employing 6 men on the 5 acres and gardened there until his death in 1859.

The economics of renting this essentially freehold land, albeit marginal in its soil condition, show why it was a good investment. When William Bower obtained the lease after a 14 year sub-let, he already had knowledge of the profitability of the property and was willing to pay a high entry fine to obtain a lease (table 4.2). Including the reserved rent, this averaged over the next 7 years to the equivalent of an annual payment of £34.4s.3d. In 1802, after 7 years had expired, payment of a renewal fine, at a much lower cost than the original entry fine, secured another 21 year period.

Despite the valuation having increased the annual economic rent, this averaged to an equivalent cost per annum of £10.13s.6d for the next 7 years. At the next seven year renewal, after another rise in valuation, the annual cost over 7 years averaged to £11.4s.2d, and gives an equivalent annual rent per acre falling from £6.16s.2d to £2.4s.10d over the 21 years.

The average annual cost decreased the longer the lease was held as the entry fine was spread over a greater length of time. There is no further information on the level of the entry fines for William’s two sons, but the longevity of the family keeping the land speaks of its value to them. Even after the bishop had had the land surveyed, and an economic rent was applied to the renewal fines, the family business continued and coped with the cycle of a high cost every 7 years followed by 6 years of low rent.

As the Bower family gardened the land for at least 79 years, over three generations, they evidently had a different opinion to the surveyor about the suitability of the location.

This analysis of the bishop’s estate confirms Clay’s findings on ecclesiastical estates that little land was rented out at rack rents, and fines did not take full account of changing interest rates, resulting in lower costs to head lessees. Only entry at the highest point in the chain of occupation at head lessee guaranteed a gardener the financial advantage of lower input costs and the long term security to make changes.

When compared to other gardeners, who were sub-letting at economic rents, head lessees benefitted from lower costs and the paternalistic approach to the management of the estate.

Even after new valuations were introduced gardeners did not give up their land; being a head lessee gave a gardener a secure tenure and sufficient economic advantage to retain the lease.

On this estate the management style undermines the ‘greedy bishop’ view of some historians. The importance to a gardener of being a head lessee of some land is emphasised by subsequent results that show only a small number of gardeners held freehold br copyhold garden land."

Conclusions

In her dissertation, she says:

1. That the Bower Family gardened the land for at least 79 years (say 1782-1861)

2. That Rowberry Mead was farmed by 3 generations. But I think it was 4:

George Bower His son William who married Elizabeth Gux Their son George who married Sarah Strudwick Their son George who married Caroline Watts

In 1861, Rowberry Mead Farm was being run by Henry Watts, Caroline's brother & Caroline and Caroline herself in 1871.

3. That William had 2 sons but I think that it was 3:

George Bower (the Eldest) William Gux Bower and Christopher Bower (Our Direct Line)

Colin Bower

5 February 2024